The Unspoken Bargain

- Ade Adegbenro

- Nov 5, 2025

- 6 min read

Ade Adegbenro (MBA ‘26) on the cost of following all the rules.

...and when the countries we worked so hard to get into shut their doors, where else does one go?

The question shadows my final days at Harvard, surfacing with each new policy announcement, each time people ask about my future plans, each piece of rhetoric from elected officials, and when I’m alone with my thoughts. It is the uncertainty that cuts beneath the satisfaction of achievement. Do I return to Africa, a continent with which I have wrestled in a fierce, lifelong tango of love and hate? Or do I swallow my pride and continue to fight for a space in societies that seem determined to remind me that full acceptance is not on the table? I am slowly coming to a sobering realization that, while others spend their lifetimes seeking purpose, some of us, it seems, may spend ours simply seeking a place to call home.

This uncertainty is made more acute because, for so long, my path was defined by a single, perhaps naïve, assumption about the societies I had worked so hard to enter. I believed that if you worked hard, followed the rules, brought valuable skills, and demonstrated an openness to be integrated, you would be welcomed. In my mind, that welcome was the quiet satisfaction of contributing to advanced research that solves some of humanity’s biggest problems, building businesses that create significant economic value and uplift society, contributing culturally to make society more diverse and beautiful, or even something as simple as the ease of a neighbor’s nod. The path of legal migration, after all, is an onerous one, a gauntlet of paperwork and scrutiny designed to select for the highly skilled who would contribute richly economically, socially, and culturally. But was I naïve to believe in this bargain, or was I gaslit into questioning a promise that was explicitly made? The visa categories themselves, like “skilled worker,” “exceptional talent,” and “Einstein Visa” seem to encode the very transaction in which I believed. I held, foolishly perhaps, that the loudest voices of opposition were aimed only at those who circumvented this process. I see now that the argument was never really about legality.

The realization leaves me unmoored. I find myself asking why this is happening now. Has the tide been turning all along, and was I too oblivious to see it? Or did something else catalyze this? The world appears to be changing at an alarming speed. It is a visceral feeling, this shift, and in my spare time, I turn to research papers and academic journals to seek answers about these currents.

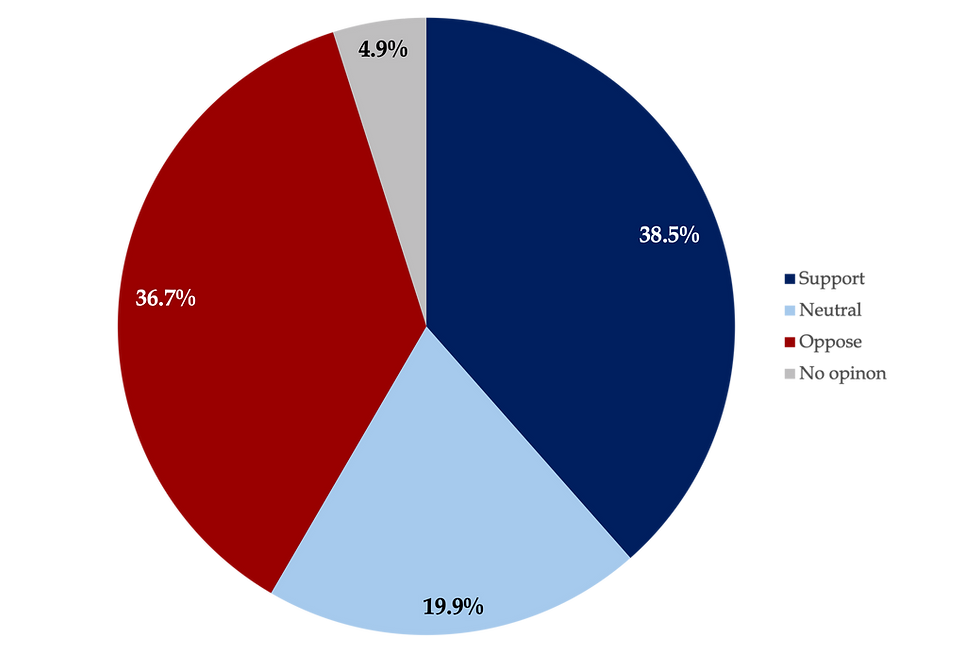

Across the West, populist nationalism that almost borders on jingoism is rising. A 2024 Gallup poll confirms that immigration has become the most important problem for Americans, eclipsing the economy. This sentiment feels familiar, echoing what researchers from HKS have observed across Europe for years. They conclude that overall cultural values, such as support for traditional values, social lifestyles, nationalism, and anti-immigration, prove strong and consistent predictors of whether Europeans support populist parties. Their findings suggest that direct economic experience, like unemployment, is a far less significant factor. This is a conclusion corroborated by research out of Cambridge that identifies deep-seated cultural concerns about immigration as the strongest predictor of far-right support.

Today, radical-right parties have successfully dragged the conversation away from policy and into the anxious realm of identity, weaving powerful narratives to drive division. This division has become a commodity — a fertile ground harvested by demagogues who profit from it, amplifying whispers into a deafening roar that they are taking your jobs and diluting your culture, pitting society against us. I know, of course, that millions stand against this tide, but their voices seem increasingly faint. And while I understand that communities feel destabilized by rapid change, I wonder if the solution is to deny the humanity of those who have already arrived and contributed, who have built lives within these societies.

We are, it seems, the generation that followed the instructions to the letter, the one that believed in the promise. We earned the most competitive grades, pursued excellence with a relentless single-mindedness, sacrificed the comfort of our youth for the promise of a foothold, and legally migrated, holding up our end of the unspoken bargain with the hope that our contributions might finally earn us a home.

But the ground in the land of our sojourn is becoming hostile. The rhetoric leaves us adrift. The prospect of return, however, is just as fraught, though I need no research to understand why. As a child, I was sold the story of an “Africa Rising,” but the continent feels stuck in a familiar cycle of squandered potential. It is the absurdity of paying $500 for a one-hour flight from Lagos to Accra, or the prohibitive expense and visa regime that makes doing business or trade within our borders impractical. It is the quiet grief of watching another brilliant mind give up and leave, defeated by a bureaucracy that prizes familial and tribal similarities over merit. But there is a more intimate and painful difficulty: the years away change you. They imbue you with a hope, an expectation of functional systems, that can feel hopelessly out of place back home. To return is to live with the ghost of the life you might have had, to carry within you a framework for a world that does not exist where you are. The opportunities to make a meaningful impact feel frustratingly out of reach. Africa, it seems, is not rising. It is failing its people, and in the process, making it impossible for some of its people to ever truly return.

And so we are caught. The person who left is not the person who can return, and we are left with a life of perpetual negotiation with our own identities. I cannot afford to be too critical of my hosts. I cannot make political commentary or hold views I can share openly, even when policies affect me directly. In the classroom, I watch what I say and how I say it. On social media, I censor what I like, what I share, what I comment. Even in writing this piece, I am chary, choosing words and statements that do not become misconstrued or taken out of context by the willfully obtuse. The calculus is constant: how much of myself can I express before I become ungrateful, divisive, a problem? And is this self-erasure a worthy price for the promise of belonging? But return means facing a different set of dysfunctions, equally profound and more intimate. It feels like a strange and profoundly sad way to live, to spend a lifetime simply searching for a place that one can call home.

Many a night, when I take my routine walk around Cambridge, soaking in the lush greenery that dots the Charles river and reflecting on my days, I find myself thinking about Kofi Awoonor’s poem, “Songs of Sorrow.” I had read it many years ago, bent over mountains of textbooks in the reading room of my boarding school as I prepared for my West African Senior Secondary Certificate Examination. Stubborn me, determined to earn the highest grade, to hear my name called at assembly, to win one more academic prize, to make my parents proud. The poem baffled me then. I could not begin to understand what Awoonor meant. Surely, I thought, if you cannot move forward, you return. If you cannot return, you go forward. My naïve, young mind could not comprehend that life often presents paradoxes with no solutions and traps with no exit. I was too consumed with the promise of a future I believed I could control to hear the poet’s warning. Now, many years later, standing on the other side of all those prizes, all those assembly celebrations, at one of the world’s most esteemed institutions, I find I have not only understood the poem’s paradox, but I also have come to inhabit it. The achievements that brought me here offer no protection from the weight of this impossible choice.

Excerpts from Kofi Awoonor’s poem, “Songs of Sorrow”:

“Dzogbese Lisa has treated me thus

It has led me among the sharps of the forest

Returning is not possible

And going forward is a great difficulty

The affairs of this world are like the chameleon feces

Into which I have stepped

When I clean it cannot go”

Ade Adegbenro (MBA ‘26) is originally West African. He has lived in 7 countries across Africa, Europe, and North America. Prior to Harvard, he worked in Growth Equity and Investment Banking. He is passionate (and critical) about Africa. Follow him on X at @degbnro.

Comments